LoL: The Best Opportunities for AI in Esports

What opportunities are there for AI to be used in League of Legends (LoL) esports? Identifying talent, winning draft, optimising items and learning better macro.

“They’re saving their last pick to counter top lane”

“It’s a safe blind-pick”

“It’s a tough match-up for X”

We hear this week-in and week-out in professional broadcasts. It is, arguably, one of the key aspects an analyst considers when deciding the strength of two rival drafts. Yet, is it really that well understood? How do we actually evaluate what makes a counter, and what impact does it have on the game?

Before we launch into this, I must make a statement to prevent a certain category of comment we often get here.

Before we launch into this, Iz must make a statement to prevent a certain category of comment we often get here.

What I mean by this, is that when I write on a specific interaction I am looking at in isolation. A players average Gold Difference at 12 minutes (GD@12) is impacted by the Champions they played, and a Champions average GD@12 is impacted by the players who piloted them.

In fact, there’s dozens of factors coming into play for every statistic. It’s not that we are ignoring them, it’s that we have to accept that they exist and then plow on regardless. Otherwise we’ll spend most of the article saying “however, we must also consider…” rather than actually discussing the metric in question.

At the end of the series (which is close), we’ll wrap all of these interactions together and evaluate their combined impact. For now, let’s keep them isolated.

With that out of the way…

How many of us rely on counter statistics to determine our Champion when jumping into a ranked game? In fact, outside of our experience on the pick and their current win rate, it’s probably the third most common statistic we all use to determine our pick.

The question is, does it apply to professional play? How valuable is it to counter a Champion? Are their certain lanes that benefit from counters more than others? How do we even evaluate a counter?

We’ll start at the last question, as it’s the foundation for everything else. The truth of the matter is, for a majority of matchups we can’t rely on data from professional games. Although it feels like we see similar compositions all the time, there’s rarely enough data each patch to be confident in the numbers from a specific match-up (i.e. Gangplank vs. Fiora). In fact, there’s barely enough data to even make assumptions about a single Champions performance (which I’ve discussed before).

Therefore, we return to solo queue (SQ). If your instincts are to sprint to the bottom of the article and angry-type “SOLO QUEUE CAN’T BE USED IN PRO THEY’RE TOO DIFFERENT”, read this article.

As per the usual caveat, we limit it to high-elo solo queue from major regions. Specifically Diamond 2+ in EUW/KR/NA, but with more weighting to Master+. I am also using professional data from the last 2.5 years. Each time taking the corresponding data from the patch in question.

We also apply some logic to our statistics by not taking the pure win rate of each pairing, but how the win rate changes from their average. For instance, if Aatrox had a 50% win rate when playing Gragas it would be easy to assume that neither counters the other.

However, if you knew Aatrox and Gragas had win rates of 55% and 45% respectively when NOT playing each other, we would say Gragas counters Aatrox — since he positively increases his win rate and decreases his opponent when they face-off. We call this statistic the “Counter Multiplier”. A 1.20x means a Champion wins that many more games compared to their average and 0.80x would mean they lose more games.

Once we have those statistics calculated for each pairing (taking into account low volume), how do they apply to professional play?

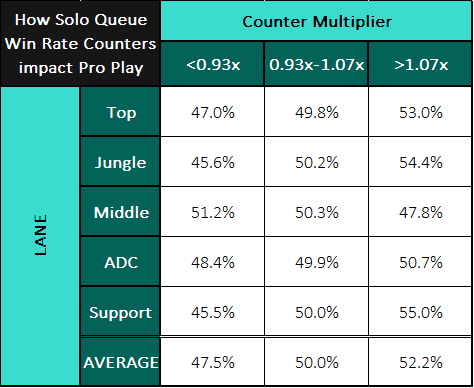

How solo-queue lane counter win rates impact professional results

The three columns indicate what the solo queue counter multiplier was for the lane match-up. Then, the average professional result are the percentages in each row.

For instance, for Jungle when the SQ counter multiplier (i.e. Jungle vs. Jungle) is less than 0.93x, the average win rate in professional play was 45.6%. When it is greater than 1.07x, it’s 54.4%.

Note, there’s at least 500 professional games per column.

Hopefully, this helps clear up the argument around whether the SQ data can even be used. If SQ and pro play had no relationship, the table would have been inconclusive. Clearly, it’s not.

The only exception being mid lane, where not only does being a strong SQ lane counter not seem to impact the professional result — but it actually suggests the reverse impact. As to why, I am unsure. Suggestions appreciated.

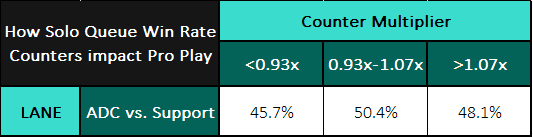

Before we close this section, I won’t create a grid to show all pairings since it would be overwhelming — but we should expect to see this impact for ADC vs. Support and vice-versa, since they interact in lane just as often as any other pairing.

How solo-queue counter win rates impact professional results in the bot lane.

With this, there’s strong evidence to suggest an ADC being hard-countered by a support has a significant effect on the win rate in pro play. However, an ADC doesn’t seem to have the same impact when they are the ones who have the high counter rating — in fact, the win rate seems to decrease again!

Now, the impact of a counter can be taken from three perspectives:

To do this, we use a similar methodology. Look at the two Champions average Gold@10 when NOT playing against each other, then how does it change when they do face-off. For instance, if a Champion had +300G vs. another, that means on average they are 300G richer than they usually are at 10 minutes.

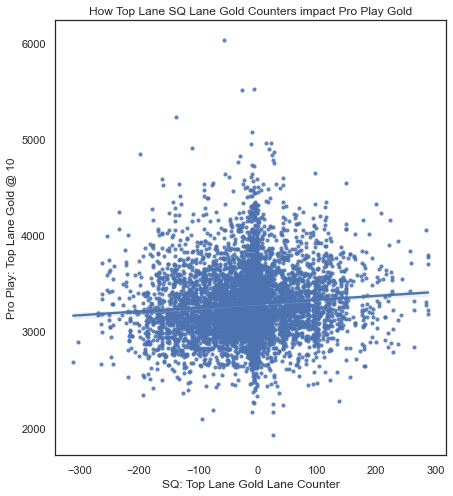

We can then plot this against the actual Gold@10 in professional play, I’ll do this for top lane — since arguably it’s the most isolated.

Note: you’ll notice a high number of Champions within the -20 to +20 mark, that’s because we adjust low volume pairs towards the mean (0).

How laning Gold in professional play is correlated to the same solo-queue statistic

As we can see, there is definitely a relationship, albeit a very weak one. There is a slight trend for Champions that do well in lane against another in SQ to also be somewhat richer for the same pairing in pro. However, it’s not to the same degree.

From a quick Linear Regression model we find that for every +100G SQ counter you can assume roughly a +40G increase in professional play. In order words, it’s about 40% as impactful.

From speaking to a few experts the common consensus is that this is caused by three factors:

With that, we draw an end to this instalment of the Esports Analyst Club, and the penultimate article on drafting. In the coming weeks I’ll be bringing all aspects impacting draft together; whether that’s countering lanes, comfort levels or champion strength. Be sure to either follow my Twitter or sign-up to the mailing list to not miss it (alongside an exciting announcement happening soon).

Here are some other articles that may be of interest.

What opportunities are there for AI to be used in League of Legends (LoL) esports? Identifying talent, winning draft, optimising items and learning better macro.

Can we use AI to predict the win rate of League of Legends (LoL) champions when they go on stage in esports games? What champions do we think will be meta? Who is the strongest?

How much does experience on a Champion matter to a winning League of Legends (LoL) esports draft? Does experience on the opposing Champion matter too?